Performing Arts -- Opera

First, there may be a handsome, sturdy young man in warrior garb somersaulting across stage and displaying his martial skills. Next, may follow a young woman veiled by strings of pearls and dressed in silk brocade singing in a gentle, feminine voice and performing a dance. Then, there is the famous Monkey King Sun Wu-k'ung with his twitching, scratching, and mischievous simian antics. These characters are all representative of China's traditional National Opera, or Peking Opera.

Librettos for Peking operas feature both tragic and comic elements, interspersed with singing, dancing, and poetic narration, to dramatize historical events and popular legends. Another style of performance features dialogue rendered in language close to everyday speech and pantomime executed with ordinary gestures. Heartwarming humor reflects and satirizes society while being educational and entertaining.

Tradition

Opera viewing has long been a popular entertainment enjoyed by both the common people as well as China's royalty and aristocracy. Also Scholars and gentry were attracted by libretto and musical score writing. The Tang Dynasty Emperor Ming Huang (712-755 A.D., also known as Hsuan Tsung) and Emperor Chuang Tsung (923-925 A.D.) of the Later Tang are considered the "honorary fathers of Chinese Opera" for their enthusiastic support of the art. Emperor Hsuan Tsung founded the Pear Garden Academy, a music and dance performing troupe within the court. In later times, opera singing was referred to as the "pear garden profession" and opera performers as "pear garden brothers."

The character roles of Peking Opera are distinguished on the basis of sex, age, and personality. The four main character types are the sheng, tan, ching, and chou.

The sheng is a male character, which is further subdivided into the elderly sheng, the young sheng, and the martial sheng. The elderly sheng is a middle-aged-to-old man who wears a beard, and delivers his lines in a serious fashion. The military sheng is skilled in martial arts; included in this category is the role of the mischievous monkey-king, Sun Wu-k'ung. The young sheng is a cultivated gentleman who often plays a dashing young lover.

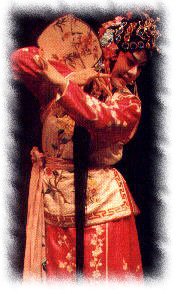

Tan refers to various female roles, including the elderly tan, the tan dressed in green, the flower tan, the sword-horse tan, and the martial tan. The elderly tan is the woman counterpart of the elderly male sheng. The tan dressed in green is a younger or middle-aged woman who is good, rational, and upright. The flower tan may be an innocent and outgoing girl or flirtatious and sassy. The military tan is a skilled fighter who often plays a female sprite in myths. The sword-horse tan is a cross between the flower tan and the martial tan; she is a female general who is bold, outgoing, and equally skilled in letters and military arts.

Although the ching and chou are supporting actors, they are still very important. The ching role is a strong-willed male character, either straightforward or scheming. His facial make-up is greatly exaggerated, so his role can be identified at a glance. The chou, or clown character is a very special one. The chou is a jocular, satirizing character who integrates his impromptu comic relief into the performance. He also steps out to make objective editorial comments on what is happening in the story.

Facial make-up in Chinese Opera, besides giving information about the personality traits and mind set of a character, also has inherent artistic interest. The designs and colors employed all have specific meanings. Red symbolizes loyalty and courage; black represents a bold and swashbuckling character; blue shows a calculating nature; and white portrays a deceitful and conniving individual. Silver and gold are reserved for the exclusive use of spirits and gods. A face that is made up in a straightforward and consistent manner is called a "complete face"; one that incorporates many diverse elements is referred to as a "fragmented face".

The costumes worn in Chinese Opera performances are broadly based on the dress in China about four centuries ago during the Ming Dynasty. Exaggerated flowing sleeves, pennants worn on the backs of military officers, and pheasant feathers used in head wear were added to heighten the dramatic effect of the stage choreography. These extra touches bring out the different levels of gestures and the rhythm of the movement. Like facial make-up, Chinese Opera costumes tell much about the character wearing them. In the past, Chinese Opera singers would rather wear a worn and torn costume than one that did not correctly represent the character he was portraying.

|

In the past, Peking Opera tended to be a "theater for actors". Actors drew on the tradition in which they were well-versed to give improvised performances. The moon lute, two-stringed violin, and drum players, who provide the musical accompaniment for the opera, had to cultivate a high degree of sensitivity to and coordination with the actors through years of working together to be able to flow with the performance.

The Present

Modern Chinese Opera, however, is now set in a box-type stage, and a director system, stage design, and professional lighting are gradually being introduced. These new features serve to enrich the performance and viewing experience without violating the traditional core of the opera.

Many contemporary opera groups attract audiences through writing of new librettos, flexible incorporation of Western theatrical concepts and functions, and experimentation with new performance techniques. Opera groups are trying to attract more young intellectuals to Peking Opera performances. An impressive new experiment has combined Western drama with traditional Chinese Peking Opera. Director Wu Hsing-kuo produced a highly innovative and successful adaption of Shakespeare's Macbeth into a modern Peking Opera. Rather than forsaking tradition, this type of experiment is an intermediary step that helps to make traditional Chinese Opera more accessible to modern audiences.

|

"Daughter of Poverty": a Beijing Opera |

Chinese Culture

Chinese Culture